Scottish Wildcat Action Plan

An action plan is a detailed technical document that precisely outlines all the steps within a conservation project.

Here you will find the outline of the project, the thinking behind it and some of the discoveries so far.

-

Wildcat Haven was initially designed by a team of experts in 2008/09. Since then, it has evolved to incorporate experiences from the fieldwork, emerging science and feedback from the local community. Designed to have the flexibility to evolve over time, the project can ensure we are always delivering the most well informed and practical conservation actions and animal welfare standards.

-

Our work includes a wide range of actions and ambitious aims including:

Saving the genetically pure Scottish wildcat

Removing all feral cats from the region

Using humane, neutering-based feral cat controls

Establishing buffer zones to prevent feral cats returning to the area

Testing for and removing feline diseases from the entire haven

Developing a genetic test for wildcat purity

Establishing project-owned wildcat reserves across the region

Documenting every individual cat in the area

Conducting unique research into cat behaviour, genetics and diseases

Building wildcat education and awareness worldwide

Encouraging reforesting to enhance natural habitat

Working alongside local communities and landowners

Advising locally owned, low impact, pro-wildcat tourism

Creating new jobs in the local community

Most importantly, Wildcat Haven seeks to create and then protect a naturally sustainable population of up to 500 pure Scottish wildcats across the West Highlands region of Scotland.

-

We have identified hybridisation as the primary threat to the Scottish wildcat. Research suggests that feral domestic cats outnumber wildcats by a ratio of at least 500:1, and perhaps by as much as 2500:1* across the Highlands.

This places the feral cat population at approximately 100,000, and the pure wildcat population between 35 and 200.

In a landscape which is home to a large, multi-generational feral cat population that is regularly supplemented by abandoned cats, town strays and farm cats, we surmised that the most practical way to save the wildcat was by focusing on establishing a small Wildcat Haven areas where all domestic cats had been neutered, local community support has been sought in ensuring all pet cats are neutered, and it is possible to protect against feral cats migrating back in.

With such a “beachhead” established, the project can then simply expand in incremental stages.

*(Harris et al 1995, Yamaguchi et al 2004, Scottish Wildcat Association 2012 unpublished)

-

We identified a location in Lochaber in the West Highlands: specifically, a peninsula with a small bottleneck landbridge, a resident pure wildcat population and relatively few feral cats.

In order to build support for the project and obtain valuable local knowledge, we engaged with the local community which has proved invaluable in the evolution of our action plan.

Domestic cats – being the primary threat to the survival of the wildcat – had to be neutered in the region as a priority. With evidence from across the globe showing that lethal-control projects often failed, we made the decision to trial a non-lethal neutering approach.

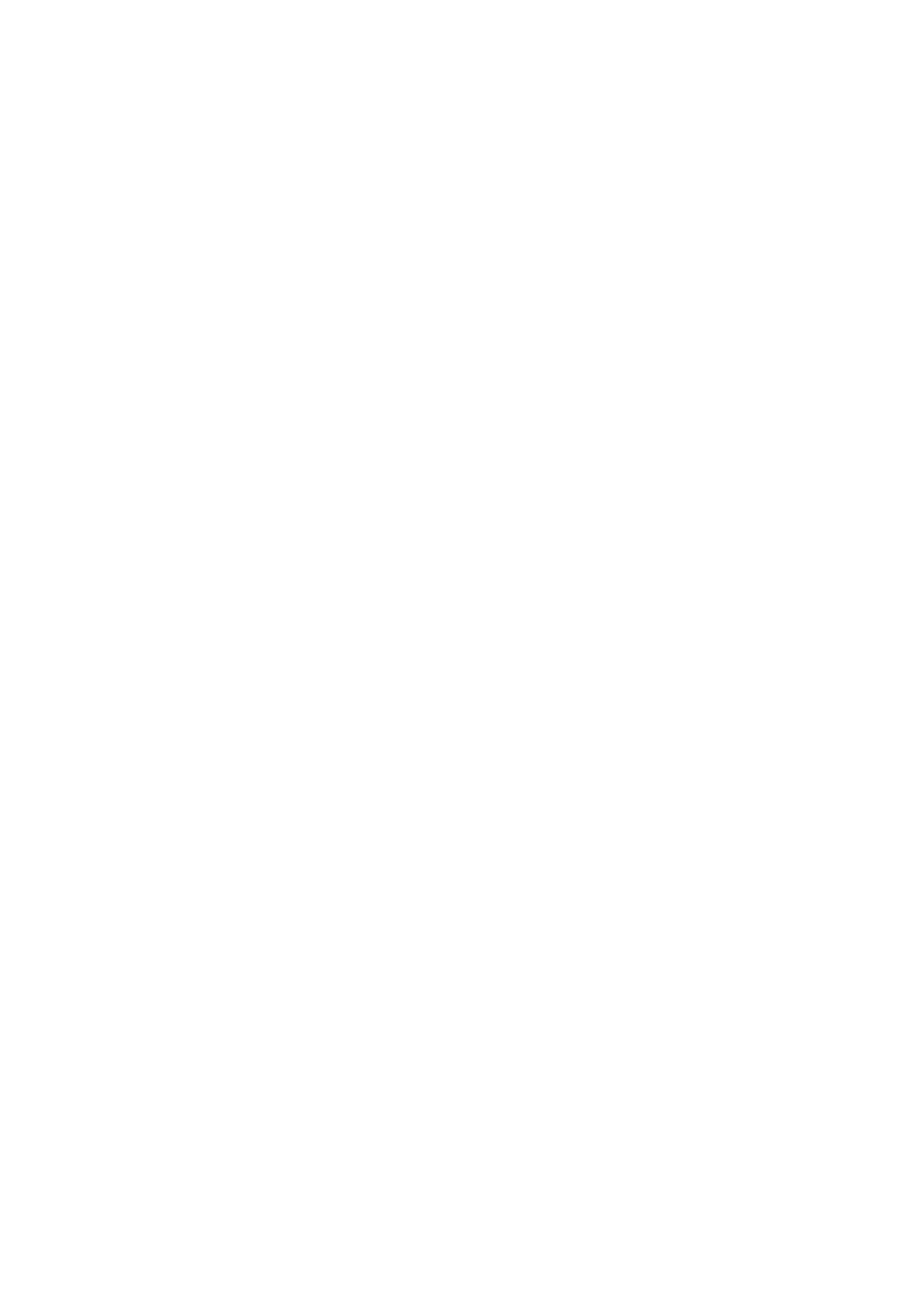

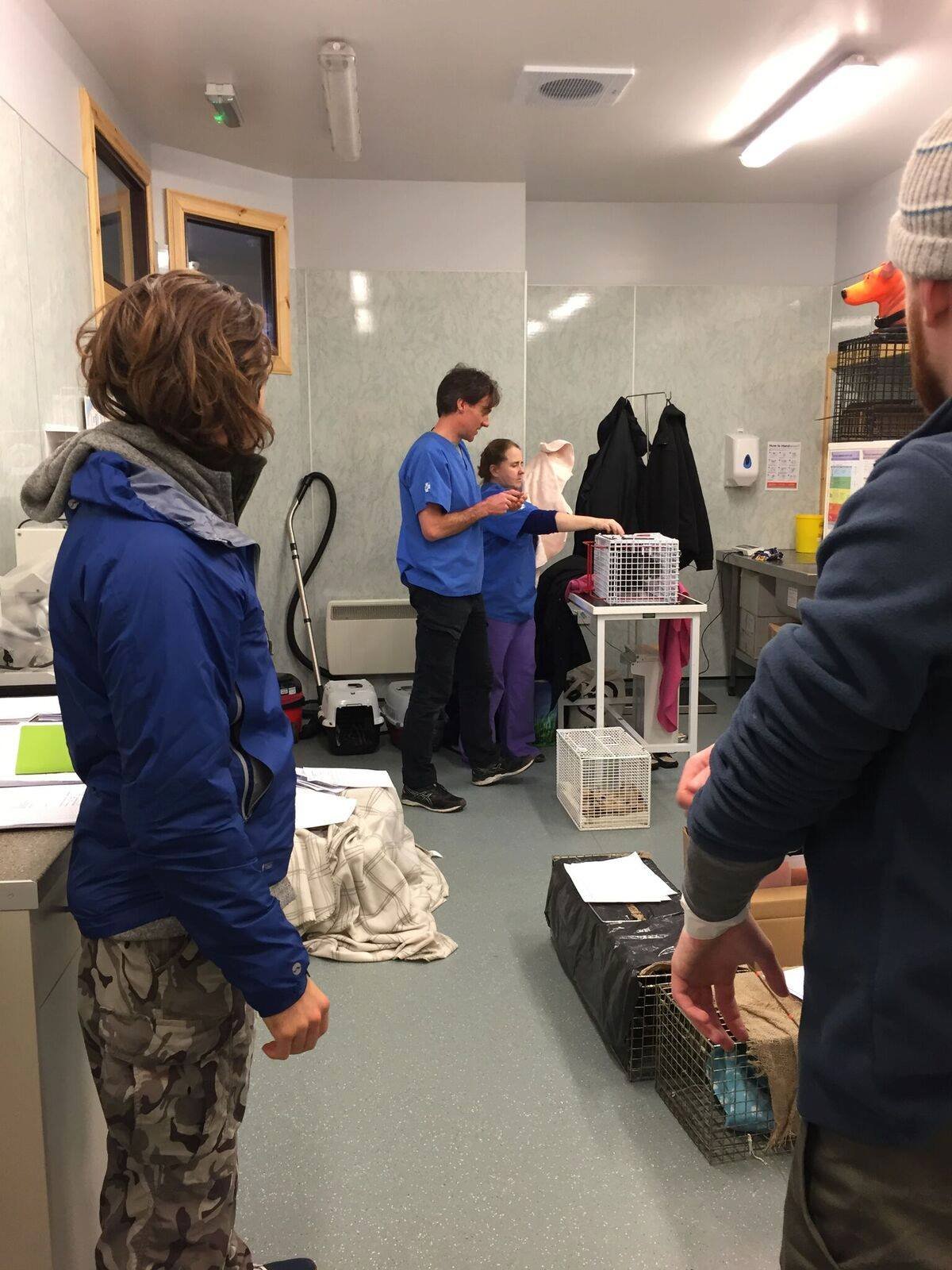

We use live trapping methods to humanely capture domestic cats in the area, which are subsequently health-checked and neutered by a vet.

-

We identified potential locations in the Highlands based on credible, reported sightings of wildcats to the Scottish Wildcat Association.

Of the potential locations, we decided that the remote peninsula of Ardnamurchan in West Lochaber was an outstanding choice from which to begin.

Arnamurchan is accessed via a small bottleneck landbridge, so if feral cats could be removed it should be relatively straightforward to keep them out simply by monitoring the bottleneck. Ardnamurchan has a resident pure wildcat population and relatively few feral cats.

-

Ardnamurchan, the remote peninsula identified as an ideal start point for Wildcat Haven.

It also benefits from a low human population, a relatively low pet cat population, limited development, few roads and a high level of awareness and concern for nature and conservation amongst the local community.

We were aware that feral cats were present in the region, living as solitary individuals and in feral cat colonies, but they appeared to be at a comparably low density.

Scottish wildcats also appeared at a low density from previous research (Scott et al 1993, unpublished) and initial surveys suggested the 2008 population lived in much the same vast territories as those measured previously.

Forestry is limited in the area but of a high quality: this is a patch of native Ardnamurchan oakwood

The large territory sizes (up to 40 square miles) appeared to be a response to low prey density, particularly rabbits, and limited forest habitat, an observation supported by local reports of unusual wildcat behaviour such as beach-combing for carrion.

Previous research into wildcat habitat and prey requirements have often been conflicting or based on unreliable data sets which featured both wildcats and hybrids. It is also plausible that behaviour varies regionally according to what is available.

Further research is ongoing to best understand wildcat requirements and any opportunities for habitat enhancement in the area. In the meantime, various re-foresting projects by local landowners and charitable organisations are already active.

This is helping to recreate the natural state of the landscape, which will dramatically improve prospects for the wildcat.

-

Ardnamurchan, Sunart, Morvern and Moidart: the ‘inland islands’ envisioned as a feral-free Scottish Wildcat Haven

The neighbouring regions of Sunart, Morvern and Moidart offered a similar geography and natural expansion opportunities. Once the success of the methodology had been confirmed (and assuming continued support from the landowners and local communities across the region), this would create a combined safe-haven of almost 1,000 square miles.

-

Engagement with the local community is a critical feature of the project.

It provides much more than access to land. It brings a great deal of local knowledge on the local ecosystem which can save years of research.

Local knowledge has led us to many of the local wildcats, hybrids and ferals, and provided insight into the kind of habitats they appeared to frequent, what kind of prey they took and so on.

-

We began by contacting local landowners, community councils, organisations and businesses. We have spent time in the area getting to know people, explaining our ideas for the project and listening to their responses and thoughts. As a result, we were subsequently able to update the action plan with the things we learned.

Many individuals raised examples of previous conservation projects by other organisations which were poorly planned, had failed to deliver positive outcomes and had made locals feel dictated to and ignored in the process.

We decided to avoid the traditional lecture-at-the-town-hall approach and looked to engage with people face-to-face; chatting with people we met along the roads or on the hill, getting coffee at the local pubs and cafes, going door-to-door to talk about the project, answering questions and taking on new information and ideas.

It was also important to work closely with animal welfare groups, pet cat owners and feral cat feeders in the area who were concerned about potential use of lethal controls on the feral cats.

We sought to assure these cat-lovers of our non-lethal approach and offered free pet cat neutering, microchipping and health checks from our field vets to help build relationships.

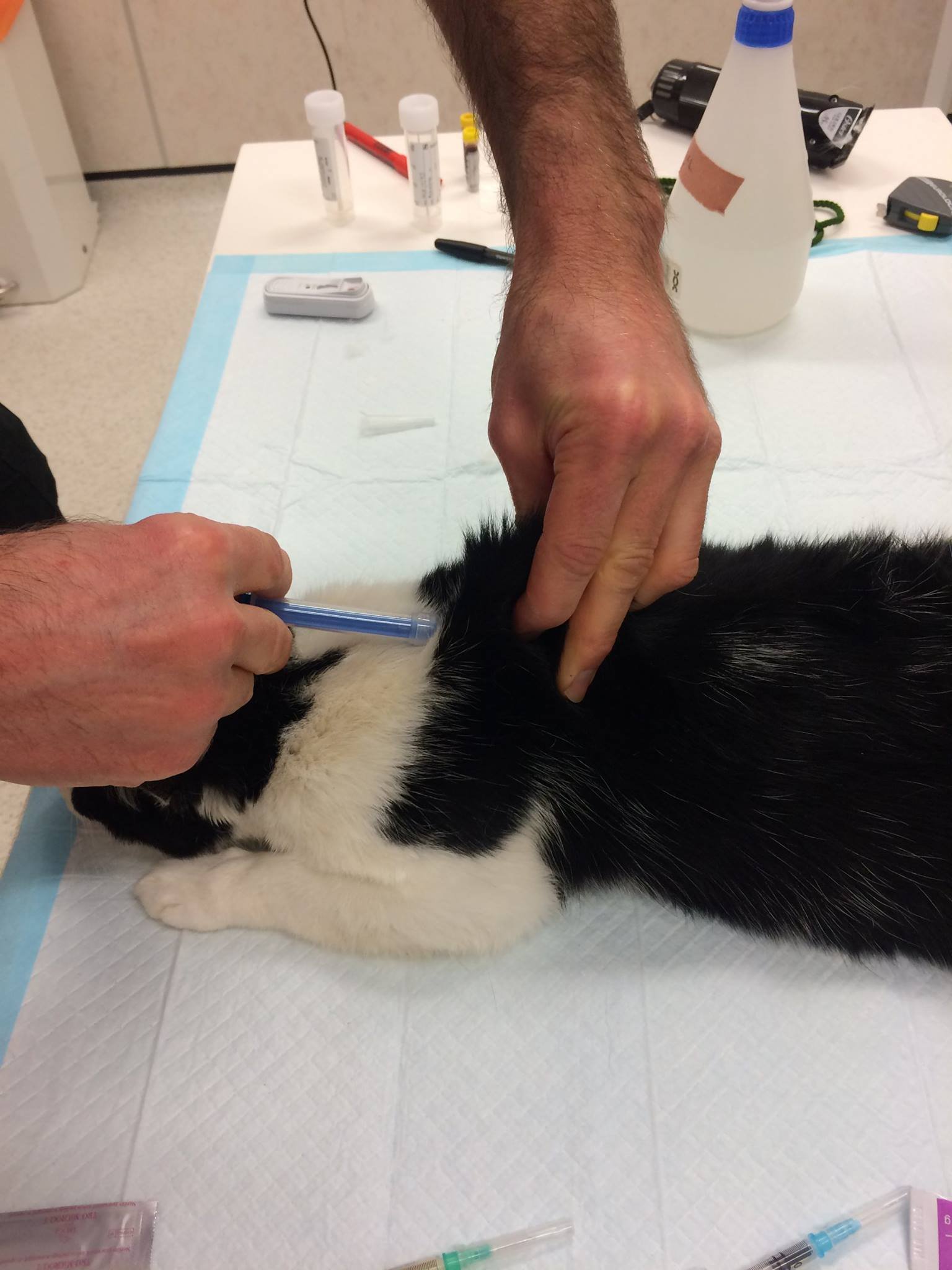

This approach had many benefits as feral cat feeders could very easily trap ferals that knew and trusted them. Local cat welfare groups had a detailed knowledge of local pet and feral cats which are dotted around the place. This assisted us in targetting locations for live trapping.

-

Recently we’ve begun working with local schools to help teach the next generation about the Scottish wildcats they’re growing up alongside. Here our Chief Scientific Adviser, Dr Paul O’Donoghue, is explaining how we use live traps to get a close up look at the various cats.

-

We hope the project can become a permanent fixture of the locality, and that it both supports the wildcats and the people that live alongside them.

Word of mouth has gradually spread, helping to build many close partnerships and relationships with the local community. Several members of the local community have offered their resources and expertise to the project, other have sought advice on running eco-tourism operations in wildcat-friendly ways.

Wildcat Haven Future Plan

They say it can’t be done, but then they also said that about neutering away feral cats: with your help Wildcat Haven can eventually cover the entire West Highlands and protect a sustainable population of Scottish wildcats forever.

Some of the other key goals that remain over the next five years include:

Habitat improvement including, restoration of native Caledonian pine forest, creation of den sites and management to increase prey species.

Neutering of all feral cats within the reserves assisting both the wildcats and other wildlife.

Establish research centres where students and visiting scientists can come to conduct research that will have a direct benefit for the wildcat. Workshops can also be carried out training volunteers and field workers with key skills to help to save the wildcat.

Establish education facilities where the public can come and learn about the Scottish wildcat and be inspired to get involved and help the wildcat themselves.

Employ local people by offering project officer and ranger posts.

Wildcat Haven deals directly with the hybridisation which is the wildcat’s greatest threat. By neutering feral cats and hybrids a vast contiguous area where wildcats can once again breed with other wildcats has been created.

Building on 7 years of field experience and by establishing strong links with the local communities, Wildcat Haven has created a template for saving the wildcat that given sufficient resources can be applied across the whole of the Western Highlands.

This is a long term vision that may take 20 years to achieve, but the result will be thousands of square miles of habitat where a truly viable population of pure wildcats can be established and protected forever.

All of the current haven activities will continue and be applied to new areas as the project spreads north and Westwards, neutralising the threat of hybridisation as we go.

A key design feature of Wildcat Haven is that it uses the natural geography to provide a modular solution. A first “module” has completed a first stage of neutering ferals and hybrids and removing feline disease, now that work can begin again on a new module, whilst the first moves into a second phase of establishing the long term monitoring and enhancement plans.

Lochaber offers several “inland island” modules, each around 200 square miles with clear geographical bottlenecked border areas which can keep feral cats from returning, and with the momentum the project currently has, the Haven can expand to cover most of that within the next five years, creating a completely safe haven for up to 100 Scottish wildcats.

Beyond that, as you look across the rest of the West Highlands there are many more modules shaped by the lochs and rugged coastline, and taking a step back you may notice that Loch Ness and Loch Lochy form the entire West Highlands into an inland island.

With just three land bridges to the mainland at Inverness, Fort Augustus and Fort William, nature has offered us 7,000 square miles of potential home we can protect for up to 1,000 wildcats: a naturally sustainable population.

Summary

Saving an isolated species means thinking big. Healthy populations need genetic diversity and space, a place to call home and that’s what Wildcat Haven is really hoping to achieve; taking the nature of the West Highlands back a few hundred years and supporting local communities to thrive amongst it.

The Scottish wildcat has spent decades on the precipice of extinction but a diverse group of people has come together to try and pull it back.

We’ve worked out how it can be done, and in the coming years, working together, we will hopefully succeed and begin the long but wonderful journey back to a healthy population and benefits for every individual life in the West Highlands.

Wildcat Haven is just the beginning of a truly holistic approach to conservation for the Scottish wildcat and all of Scotland’s amazing natural heritage.